si no está usando regularmente un medicamento opioide prescrito por su médico (p. ej., codeína, fentanilo, hidromorfona, morfina, oxicodona, meperidina), todos los días a la misma hora, al menos durante una semana, para controlar el dolor persistente. Si no ha estado usando esos medicamentos, no use Actiq dado que su uso puede aumentar el riesgo de que su respiración se vuelva más lenta y/o superficial, e incluso de que llegue a pararse

si es alérgico al fentanilo, oa cualquiera de los demás componentes de este medicamento (incluidos en la Sección 6).

si está actualmente tomando medicamentos inhibidores de monoamina-oxidasa (IMAO) para el tratamiento de la depresión grave (o lo ha hecho hace menos de 2 semanas).

si padece problemas respiratorios graves o una afección pulmonar obstructiva grave.

si padece dolor de corta duración distinto al dolor irruptivo

No utilice Actiq si se encuentra en cualquiera de los casos anteriores. Si no está seguro, consulte a su médico o farmacéutico antes de utilizar Actiq.

Advertencias y precauciones:

Durante el tratamiento con Actiq siga utilizando el medicamento opioide analgésico que toma para su dolor persistente (presente todo el tiempo) asociado al cáncer.

Consulte a su médico o farmacéutico antes de empezar a usar Actiq si:

El otro medicamento opioide que toma para su dolor persistente (presente todo el tiempo) asociado al cáncer aún no se ha estabilizado.

Usted sufre alguna enfermedad que le afecta la respiración (como asma, silbidos respiratorios, o falta de aliento).

Tiene alguna lesión en la cabeza o ha sufrido alguna pérdida de conciencia.

Tiene problemas de corazón, especialmente frecuencia cardíaca baja.

Tiene problemas del hígado o riñones, ya que estos afectan el modo en que el organismo elimina el medicamento.

Tiene la presión sanguínea baja debido a un bajo volumen de líquido en el sistema circulatorio.

Tiene más de 65 años, ya que puede ser preciso disminuir la dosis. Cualquier incremento en la dosis deberá ser cuidadosamente supervisado por su médico.

Toma antidepresivos o antipsicóticos; consulte la sección “Uso de otros medicamentos”.

Actiq contiene aproximadamente 2 gramos de azúcar y un consumo frecuente le exponen a un aumento del riesgo de caries dental que puede ser importante. Por tanto, es importante continuar teniendo buen cuidado de su boca y dientes durante el tratamiento con Actiq. Consulte con su médico si presenta tales efectos locales importantes.

Actiq no está recomendado para niños menores de 16 años de edad.

Este medicamento contiene fentanilo que puede producir un resultado positivo en las pruebas de control de dopaje.

Uso de Actiq con otros medicamentos

No use este medicamento e informe a su médico o farmacéutico si está tomando:

Otros tratamientos a base de fentanilo que le hubieran prescrito anteriormente para el dolor irruptivo. Si aún conserva estos productos de fentanilo en casa, contacte con el farmacéutico quien le indicará cómo desprenderse de ellos.

Informe a su médico o farmacéutico si está utilizando o ha utilizado recientemente o podría tener que utilizar cualquier otro medicamento, incluso los adquiridos sin receta y las plantas medicinales. En particular, informe a su médico o farmacéutico si está utilizando alguno de los siguientes medicamentos:

Algún medicamento que pueda producirle sueño, como píldoras para dormir, medicamentos para tratar la ansiedad, algunos medicamentos para tratar la alergia (antihistamínicos) o tranquilizantes.

Ciertos relajantes musculares, como baclofeno o diazepam.

Algún medicamento que pueda afectar al modo en que el organismo elimina Actiq, tales como ritonavir u otros medicamentos que ayudan a controlar la infección por el virus VIH (SIDA) u otros medicamentos denominados “inhibidores de la CYP3A4” como el ketoconazol, itraconazol o fluconazol (utilizados para las infecciones por hongos) y troleandomicina, claritromicina o eritromicina (medicamentos para las infecciones bacterianas) y los llamados “inductores”. de CYP3A4” como rifampicina o rifabutina (medicamentos para las infecciones bacterianas), carbamazepina, fenobarbital o fenitoína (medicamentos utilizados para tratar las convulsiones/ataques)

Cierto tipo de analgésicos potentes, llamados agonistas/antagonistas parciales, como la buprenorfina, la nalbufina y la pentazocina (medicamentos para tratar el dolor). Mientras utiliza estos medicamentos, podría presentar síntomas de un síndrome de abstinencia (náuseas, vómitos, diarrea, ansiedad, escalofríos, temblor y sudoración).

Si debe someterse a una cirugía que requiera anestesia general.

El riesgo de efectos adversos aumenta si está tomando medicamentos tales como ciertos antidepresivos o antipsicóticos. Actiq puede interactuar con estos medicamentos y usted puede presentar cambios en el estado mental (p. ej., agitación, alucinaciones, coma) y otros efectos como temperatura corporal mayor de 38°C, aumento de la frecuencia cardíaca, presión arterial inestable y exageración de los reflejos, rigidez muscular, falta de coordinación y/o síntomas gastrointestinales (p. ej., náuseas, vómitos, diarrea). Su médico le dirá si Actiq es adecuado para usted.

Uso de Actiq con alimentos, bebidas y alcohol

Actiq puede usarse antes o después de las comidas. Sin embargo, no lo utilice durante una comida.

Puede beber un poco de agua antes de usar Actiq para humedecerse la boca. Sin embargo, no debe beber ni comer nada mientras usa Actiq.

No tome zumo de pomelo mientras usa Actiq ya que puede tener efecto sobre el modo en que el organismo elimina Actiq.

No tome bebidas alcohólicas mientras esté en tratamiento con Actiq ya que puede aumentar las probabilidades de sufrir graves efectos adversos.

Embarazo, lactancia y fertilidad

Si está embarazada o en período de lactancia, cree que podría estar embarazada o tiene intención de quedarse embarazada, consulte a su médico o farmacéutico antes de utilizar este medicamento.

No utilice Actiq durante el parto porque puede provocar dificultades respiratorias en el recién nacido. Hay también un riesgo de que el recién nacido sufra síndrome de abstinencia si durante el embarazo ha utilizado Actiq durante largos períodos de tiempo.

El fentanilo puede pasar a la leche materna y causar efectos adversos en el lactante. No use Actiq si está dando el pecho a su hijo. No debe iniciar la lactancia antes de transcurridos al menos 5 días desde la última dosis de Actiq.

Consulte a su médico o farmacéutico antes de utilizar cualquier medicamento, si está embarazada o en período de lactancia.

Conducción y uso de máquinas

Este medicamento puede afectar su habilidad para conducir o manejar determinadas herramientas o maquinaria. Consulte con su médico sobre la seguridad para usted de conducir o manejar determinadas herramientas o maquinaria en las horas siguientes al uso de Actiq.

No conduzca o maneje determinadas herramientas o maquinaria si: se siente adormecido o mareado; tiene visión borrosa o doble visión; Tiene dificultad en concentrarse. Es importante que conozca cómo le afecta Actiq antes de conducir o manejar determinadas herramientas o maquinaria.

Actiq contiene glucosa y sacarosa (tipos de azúcar)

Si su médico le ha indicado que padece una intolerancia a ciertos azúcares, consulte con él antes de usar este medicamento.

Los pacientes con diabetes mellitus deben tener en cuenta que este medicamento contiene aproximadamente 2 gramos de glucosa por cada comprimido para chupar.

La glucosa que contienen los comprimidos para chupar de Actiq puede ser perjudicial para sus dientes. Debe siempre asegurarse de que se ha limpiado los dientes regularmente.

Siga exactamente las instrucciones de administración de este medicamento indicadas por su médico. En caso de duda, consulte de nuevo a su médico o farmacéutico.

Cuando comience a utilizar Actiq por primera vez, su médico colaborará con usted para encontrar la dosis de Actiq que le aliviará el dolor irruptivo. Es muy importante que utilice Actiq exactamente como lo ha indicado su médico.

No cambie por su cuenta las dosis de Actiq ni de otros analgésicos. Cualquier cambio en la dosificación tiene que ser prescrito y vigilado por su médico.

Si tiene dudas sobre la dosis correcta o si tiene preguntas sobre el uso de Actiq, consulte a su médico.

Cómo penetrar el medicamento en el organismo

Cuando usted pone Actiq en la boca:

El comprimido para chupar se disuelve, y la sustancia activa se libera. Este proceso tiene lugar en unos 15 minutos.

La sustancia activa es absorbida a través de la mucosa oral hacia la circulación sanguínea.

El hecho de usar el medicamento de dicha forma permite que se absorba rápidamente, lo que significa un alivio rápido del dolor irruptivo.

Determinación de la dosis correcta

Debería empezar a sentir alivio rápidamente mientras usa Actiq. No obstante, hasta que usted y su médico determinen la dosis que controla eficazmente el dolor irruptivo, es posible que no sienta un alivio suficiente del dolor 30 minutos después de haber comenzado a utilizar una unidad de Actiq (15 minutos desde que acaba de utilizar el comprimido de Actiq). Si esto ocurre, su médico le puede permitir utilizar un segundo comprimido de Actiq de la misma dosis para tratar un mismo episodio de dolor irruptivo.

No utilice una segunda unidad a menos que se lo indique su médico. Nunca utilice más de dos unidades para tratar un solo episodio de dolor irruptivo.

Durante la determinación de la dosis correcta, es posible que necesite disponer de unidades de Actiq de distintas concentraciones en su domicilio. Sin embargo, conserve en casa únicamente las concentraciones de Actiq que necesite. Esto permite prevenir posibles confusiones y sobredosis. Consulte con el farmacéutico cómo desprenderse de las unidades de Actiq que no necesita.

¿Cuántas unidades se deben utilizar?

Una vez que haya determinado la dosis correcta con su médico, use 1 unidad para un episodio de dolor irruptivo. Consulte con su médico si su dosis correcta de Actiq no le alivia el dolor irruptivo a lo largo de varios episodios consecutivos de dolor irruptivo. Su médico decidirá si es preciso modificarle la dosis.

Debe comunicarse enseguida a su médico si usa Actiq más de cuatro veces al día. En ese caso quizás crea cambiar convenientele el medicamento para el dolor persistente (presente todo el tiempo). Una vez hecho, cuando se le haya controlado el dolor persistente, puede que el médico deba volver a cambiarle la dosis de Actiq. Para obtener mejores resultados, informe a su médico sobre el dolor que padece y sobre cómo está actuando Actiq. De este modo se podrá cambiar la dosis si resulta necesario.

Apertura del envoltorio – Cada unidad de Actiq está sellada en su propio envoltorio blister.

Abra el envoltorio cuando esté preparado para utilizarlo. No lo abra antes de tiempo

Sujete el envoltorio blíster con el lado impreso opuesto a usted.

Sujete el extremo corto del envoltorio blister.

Coloque las tijeras cerca del extremo de la unidad Actiq y corte completamente el extremo largo (vea la ilustración).

Separe la parte posterior impresa del envoltorio blister y extraigala completamente del envoltorio.

Saque la unidad de Actiq del envoltorio blister y acto seguido coloque el comprimido de Actiq en la boca.

Uso de la unidad de Actiq

Coloque el comprimido para chupar entre las mejillas y las encías. Con el aplicador, desplace continuamente Actiq por la boca, especialmente por las mejillas. Gire el aplicador a menudo.

Para que el alivio sea más eficaz, debe acabarse totalmente la unidad de Actiq en unos 15 minutos. Si la termina demasiado rápido, tragará más medicamentos y obtendrá menos alivio del dolor irruptivo.

No muerda, chupe, ni mastique la unidad de Actiq. Esto se traduciría en menores niveles en sangre y menor alivio del dolor que si se utiliza según se indica.

Si por alguna razón no termina toda la unidad de Actiq cada vez que sufre dolor irruptivo, póngase en contacto con su médico.

Frecuencia de administración

Una vez que haya obtenido una dosis que le controle eficazmente el dolor, no utilice más de cuatro unidades de Actiq al día. Si cree que quizás necesita más de cuatro unidades de Actiq diarias, debe notificárselo de inmediato a su médico.

¿Cuántas unidades de Actiq debes usar?

No utilice más de dos comprimidos para chupar de Actiq para tratar un solo episodio de dolor irruptivo.

Si usa más Actiq del que debía

Los efectos adversos más habituales si usa demasiado son somnolencia, mareos y náuseas.

Si empieza a sentirse mareado, con ganas de vomitar o con mucho sueño antes de que el comprimido para chupar se haya disuelto completamente, retírelo de la boca y pida a otra persona de la casa que le ayude.

Un efecto adverso grave de Actiq es la respiración lenta y/o poco profunda. Esto puede ocurrir si la dosis de Actiq es demasiado elevada o si usted usa demasiado Actiq.

Si esto ocurriera busque asistencia médica enseñada.

En caso de sobredosis o ingestión accidental, consulte a su médico o farmacéutico o llame al Servicio de Información Toxicológica. Teléfono: +34 91 562 04 20, indicando el medicamento y la cantidad ingerida.

Qué hacer si un niño o un adulto usa accidentalmente Actiq

Si cree que alguien ha usado Actiq accidentalmente, busque asistencia médica enseguida. Intente mantener la persona despierta (llamándola por su nombre o sacudiéndola por el brazo o el hombro) hasta que llegue la asistencia médica.

Si todavía persiste el dolor irruptivo, debe usar Actiq según le haya indicado su médico. Si el dolor irruptivo desaparece, no use más Actiq hasta que aparezca otro episodio de dolor irruptivo.

Si interrumpe el tratamiento con Actiq

Debe suspender Actiq cuando ya no tenga ningún dolor irruptivo. Sin embargo, debe seguir tomando su medicamento analgésico opioide habitual para tratar el dolor canceroso persistente, tal como le ha indicado su médico. Cuando suspenda el tratamiento con Actiq, puede presentar síntomas de abstinencia similares a los posibles efectos adversos de Actiq. Si presenta síntomas de abstinencia o si le preocupa el alivio del dolor, debe consultar a su médico. Su médico evaluará si necesita medicamentos para reducir o eliminar los síntomas de abstinencia.

Si tiene cualquier otra duda sobre el uso de este medicamento, pregunte a su médico o farmacéutico.

4. Posibles efectos adversos

Al igual que todos los medicamentos, este medicamento puede producir efectos adversos, aunque no todas las personas los sufran. Si nota algún efecto adverso, contacte con su médico. Los efectos adversos más graves son respiración poco profunda, tensión arterial baja y shock.

Usted o su cuidador deben retirar la unidad de Actiq de la boca. Contacte con su médico inmediatamente y solicite ayuda urgente si usted experimenta alguno de los siguientes efectos adversos – es posible que necesite atención médica urgente:

Si está muy somnoliento o tiene una respiración lenta o poco profunda.

Dificultad para respirar o mareos, aumento de la lengua, labios o garganta que pueden ser los primeros signos de una reacción alérgica grave.

Nota para las personas que le cuiden:

Si observa que el paciente que usa Actiq tiene una respiración lenta y/o poco profunda o si le cuesta despertarle, tome INMEDIATAMENTE las siguientes medidas:

Coja la unidad de Actiq por el aplicador, quítesela al paciente de la boca y manténgala fuera del alcance de los niños o de los animales de compañía hasta que la deseche.

SOLICITAR ASISTENCIA DE URGENCIA

Mientras espera que llegue la asistencia de urgencia, si parece que la persona respira lentamente, incítela a respirar cada 5–10 segundos.

Si se siente excesivamente mareado, somnoliento o experimenta cualquier otro malestar mientras usa Actiq, retire la unidad de Actiq de la boca utilizando el aplicador y deséchela según las instrucciones explicadas en este prospecto (ver sección 5). A continuación, póngase en contacto con su médico para que le dé nuevas instrucciones de uso de Actiq.

Efectos adversos muy frecuentes (pueden afectar a más de 1 de cada 10 personas):

Vómitos, náuseas/malestar, estreñimiento, dolor estomacal (abdominal)

Astenia (debilidad), somnolencia, sedación, mareos, dolor de cabeza.

Efectos adversos frecuentes (pueden afectar hasta 1 de cada 10 personas):

Confusión, ansiedad, ver o escuchas cosas que no están (alucinaciones), depresión, cambios de humor.

Espasmo muscular, sensación de vértigo o de mareo, pérdida de conciencia, sedación, sensación de hormigueo, entumecimiento, dificultad para coordinar movimientos, aumento o alteraciones de la sensibilidad al tacto, convulsiones (crisis epilépticas).

Sequedad de boca, inflamación bucal, afecciones de la lengua (por ejemplo sensación de ardor o úlceras), alteraciones del gusto.

Gases, aumento abdominal, indigestión, disminución del apetito, pérdida de peso.

Sudoración, erupciones cutáneas, picor cutáneo.

Lesiones accidentales (por ejemplo, caídas).

Efectos adversos poco frecuentes (pueden afectar hasta 1 de cada 100 personas):

Caries dental, parálisis del intestino, úlceras en la boca, sangrado de las encías.

Coma, dificultad para hablar.

Sueños anormales, sensación de indiferencia, pensamientos anormales, sensación excesiva de encontrarse bien.

Dilatación de los vasos sanguíneos.

También se han notificado los siguientes efectos adversos con el uso de Actiq pero se desconoce la frecuencia con la que pueden ocurrir:

Disminución de las encías, inflamación de las encías, pérdida dental, problemas respiratorios graves, rubor, sensación de mucho calor, diarrea, inflamación de brazos o piernas, fatiga, insomnio, pirexia, síndrome de abstinencia (puede manifestarse por la aparición de efectos adversos de tipo náuseas, vómitos, diarrea, ansiedad, escalofríos, temblor y sudoración)

Mientras utiliza Actiq puede experimentar irritación, dolor y úlceras en el lugar de aplicación y sangrado de encías.

Comunicación de efectos adversos

Si experimenta cualquier tipo de efecto adverso, consulte a su médico o farmacéutico, incluso si se trata de posibles efectos adversos que no parecen en este prospecto. También puede comunicarlos directamente a través del Sistema Español de Farmacovigilancia de Medicamentos de Uso Humano: https://www.notificaram.es Mediante la comunicación de efectos adversos usted puede contribuir a proporcionar más información sobre la seguridad de este medicamento.

El medicamento analgésico de Actiq es muy potente y podría resultar potencialmente mortal para un niño si lo usa accidentalmente. Actiq debe mantenerse fuera de la vista y del alcance de los niños.

No utilice Actiq después de la fecha de caducidad que aparece en el envase blister y el cartonaje. La fecha de caducidad es el último día del mes que se indica.

Conservar por debajo de 30ºC.

Mantenga Actiq siempre en su envoltorio blister hasta que esté preparado para usarlo. No use Actiq si el envoltorio blister está dañado o abierto antes de que usted esté listo para usarlo.

Si ha dejado de utilizar Actiq, o si bien tiene unidades no usadas de Actiq en casa, devuelva todas las unidades no usadas a su farmacéutico.

Cómo eliminar Actiq una vez usado

Las unidades parcialmente utilizadas de Actiq pueden contener todavía suficiente medicamento como para resultar nocivas o potencialmente mortales en un niño.

Incluso tanto si queda algo de medicamento como si no en el aplicador, el aplicador debe eliminarse apropiadamente, de la siguiente forma:

Si no queda nada de medicamento, tire el aplicador a un contenedor de basura que esté fuera del alcance de los niños y animales de compañía.

Si queda medicamento en el aplicador, coloque el comprimido debajo de un grifo de agua caliente para disolver los restos y luego tire el aplicador a un contenedor de basura que esté fuera del alcance de los niños y animales de compañía.

Si no termina toda la unidad de Actiq y no puede disolver los restos de medicamento inmediatamente, ponga la unidad de Actiq fuera del alcance de los niños y animales de compañía hasta que disponga de tiempo para desechar la unidad de Actiq parcialmente empleada según se ha explicado.

No tire por el WC las unidades de Actiq parcialmente empleadas, los aplicadores de Actiq ni el envoltorio blister.

6. Contenido del envase e información adicional

El principio activo es fentanilo. Cada comprimido para chupar contiene:

200 microgramos de fentanilo (como citrato)

400 microgramos de fentanilo (como citrato)

600 microgramos de fentanilo (como citrato)

800 microgramos de fentanilo (como citrato)

1.200 microgramos de fentanilo (como citrato)

1.600 microgramos de fentanilo (como citrato).

Los demás componentes son:

Dextratos hidratados (equivalente a aproximadamente 2 gramos de glucosa).

Ácido cítrico, fosfato disódico, sabor artificial de baya (maltodextrina, propilenglicol, aromas artificiales y trietilcitrato), estearato de magnesio.

Adhesivo comestible utilizado para pegar el comprimido al aplicador:

Almidón comestible a base de maíz modificado (E 1450), azúcar glaseado (como sacarosa y almidón de maíz), agua.

Agua, goma laca blanca desencerada, propilenglicol y colorante azul alquitrán de hulla sintético (E 133).

Aspecto del producto y contenido del envase

Actiq es un sistema para la administración de medicamentos directamente a través de la mucosa oral. Cada unidad de Actiq se compone de un medicamento sólido de color blanco unido a un aplicador.

La unidad normalmente es blanca, sin embargo, durante el almacenamiento puede adquirir un aspecto ligeramente moteado. Esto se debe a ligeros cambios en el aromatizante del producto y no afecta en modo alguno la acción del medicamento.

Actiq existe en 6 dosis diferentes: 200, 400, 600, 800, 1200 y 1600 microgramos. La dosis está marcada en el comprimido blanco, en el aplicador, en el blister y en el cartón, para garantizar que usted use el medicamento y la dosis adecuada. Cada dosis está asociada a un color específico.

Cada envoltorio blister contiene una sola unidad de Actiq.

Los blíster se suministran en cajas de 3,6, 15 ó 30 unidades individuales de Actiq. Puede que solamente estén comercializados algunos tamaños de envases.

Titular de la autorización de comercialización y responsable de la fabricación

Titular de la autorización de comercialización: Teva Pharma BV Swensweg 5, 2031 GA Haarlem Holanda

Responsable de la fabricación: Teva Pharmaceuticals Europe BV Swensweg 5, 2031 GA Haarlem

Holanda

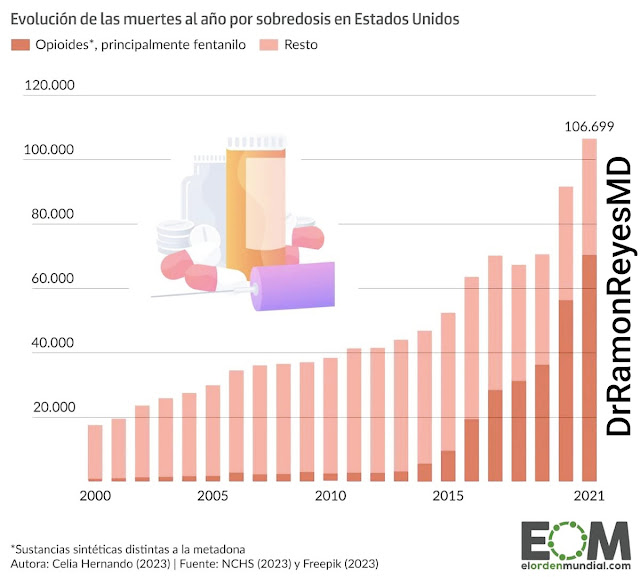

#Drogas La #heroína El #fentanil El #carfentanil http://emssolutionsint.blogspot.com/2018/04/fentanilo-oral-transmucosa-uso-en-tccc.html En la imagen son dosis de distintas drogas, en la cantidad requerida para terminar con la vida de un ser humano. La #heroína es una droga derivada del opio, utilizada en el ámbito del sector salud por sus propiedades analgésicas, y socialmente como droga recreativa por sus efectos. El #fentanil es una droga opiácea sintética, con una potencia aproximada 100 veces superior a la heroína, utilizada en el ámbito del sector salud con el fin de anular/disminuir el dolor crónico diverso. El #carfentanil , de igual manera es una droga sintética opiácea, es aproximadamente 100 veces más potente que el fentanil, y suele ser utilizado en el ámbito veterinario, con el fin de sedar/adormecer animales de gran tamaño/peso...

|

| FENTANILO ORAL TRANSMUCOSA uso en TCCC y TECC |

La información detallada y actualizada de este medicamento está disponible en la página Web de la Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios (AEMPS) http://www.aemps.gob.es/

– Analgésico opiáceo, agonista de receptores mu-opiáceos. El fentanilo es un derivado de fenilpiperidina que se comporta como agonista puro de los receptores mu opiáceos presentes en el cerebro, la médula espinal y el músculo liso. Se desconoce cómo actúa, si bien se ha sugerido que los opiáceos imitarían los efectos de las endorfinas, opiáceos endógenos. La unión al receptor ocasionaría una hiperpolarización, que inhibiría la descarga espontánea neuronal. También podrían alterar el transporte de los iones calcio, y controlar la liberación de neurotransmisores al modificar las características de la membrana plasmática.

Fentanilo disminuye la transmisión nerviosa del dolor, por lo que se comporta como un poderoso analgésico, considerándose hasta 100 veces más potente que la morfina. Su efecto es dosis-dependiente, apareciendo analgesia a Cp de 1-2 ng/ml en pacientes no tratados previamente con opioides, mientras que a 10-20 ng/ml se produce una profunda depresión nerviosa, que da lugar a anestesia quirúrgica y depresión respiratoria profunda. Al igual que otros opioides, da lugar a tolerancia por lo que estas concentraciones van siendo cada vez mayores según se prolonga su utilización.

Debido a su gran liposolubilidad, presenta unos efectos analgésicos rápidos pero poco duraderos, aunque en administración repetida tiende a acumularse en el tejido adiposo, prolongándose sus efectos.

Los efectos no selectivos del fentanilo sobre otras vías de transmisión nerviosa ocasionan la aparición de otros efectos secundarios, y por regla general adversos, tales como disminución del peristaltismo intestinal, que da lugar al estreñimiento por opiáceos, aumento del tono del músculo liso urinario, con efectos variables desde urgencia urinaria a retención urinaria, depresión respiratoria dosis dependiente, aparición de dependencia física y adicción.

– Absorción: Tras la administración de una tableta sublingual, bucal o para chupar, se produce la liberación del fentanilo en la cavidad oral (en el caso de los comprimidos bucales, se produce una reacción efervescente que aumenta la velocidad y el grado de absorción). Parte de este fentanilo se absorbe rápidamente a través de la mucosa oral (25% en comprimidos para chupar, 48% en comprimidos bucales, 51% en película bucal) mientras que el resto es deglutido y se absorbe a nivel intestinal mucho más lentamente. El fentanilo sufre un intenso efecto de primer paso intestinal y hepático, por lo que de la dosis deglutida sólo llega a circulación sistémica alrededor del 30%. Su biodisponibilidad es del 50% (comprimidos para chupar), 65% (comprimidos bucales), 75% (comprimidos sublinguales) 71% (película bucal). Tras la administración de una dosis de 200-1600 mcg (comprimidos para chupar) se alcanza una Cmax de 0,39-2,51 ng/ml a los 20-40 min (en algunos pacientes se alcanza a los 480 minutos); en el caso de dosis de 100-800 mcg sublinguales, la Cmax de 0,2-1,3 ng/ml se consigue a los 30 min (pudiéndose prolongar en ciertos pacientes hasta 240 min); en dosis de 400 mcg bucales, la Cmax de 1,02 ng/ml se alcanza a los 45 min (en algunos casos el tmax se ha llegado a prolongar hasta 240 min). Película bucal: Con dosis de 200-1200 mcg la Cmax alcanzada es de 0.38-2,19 ng/ml, Tmax: 45-240 minutos (media 60 minutos),

– Distribución: Es un fármaco muy liposoluble por lo que se va a distribuir rápidamente a cerebro, corazón, pulmones, riñón y bazo, y de forma más lenta a músculo y tejido adiposo, donde tiende a acumularse. Se une 80-85% a proteínas plasmáticas, mayoritariamente alfa1-glicoproteína ácida, y en menor medida a albúmina y lipoproteínas. Vd 3-6 l/kg.

– Metabolismo: Intenso metabolismos intestinal y hepático a través del CYP3A4, dando lugar a metabolitos inactivos como norfentanilo.

– Eliminación: Se elimina mayoritariamente en orina (75% de la dosis a las 72 h) en forma de metabolitos, con < 10% en forma inalterada. También minoritariamente en heces (9%) como metabolitos (<1 20="" 7="" 8="" bucales="" chupar="" clt="" comprimidos="" de="" es="" h="" hasta="" inalterado="" kg.="" min="" ml="" para="" presenta="" span="" su="" sublinguales="" t1="" una="" unas="" y="">

– [DOLOR]. Tratamiento de las crisis de dolor irruptivo en adultos con cáncer tratados con opiáceos, en los que aparecen exacerbaciones dolorosas que no puedan ser controladas por el tratamiento analgésico habitual.

La dosis de fentanilo se individualizará en función de la situación clínica de cada paciente.

– Adultos, bucal: El tratamiento se iniciará sólo si el paciente tolera los opiáceos (en tratamiento con 60 mg/24 h de morfina oral, 25 mcg/h de fentanilo transdérmico o una potencia similar de otro opiáceo durante una semana o más). * Actiq: inicialmente 1 comprimido (200 mcg) ante cada brote de dolor irruptivo. Esta dosis se irá incrementando hasta alcanzar la dosis eficaz, que es aquella dosis mínima que permita controlar el dolor irruptivo con un solo comprimido.

Cálculo de la dosis eficaz: Si a los 15 minutos de terminar de chupar el comprimido no se consigue la eficacia analgésica deseada, se administrará un nuevo comprimido de igual dosis. En el caso de que se necesite más de un comprimido para tratar dos episodios consecutivos de dolor irruptivo, se incrementará la dosis a la siguiente concentración disponible, hasta alcanzar la dosis eficaz. Muy pocos pacientes requieren dosis adicionales con los comprimidos de 1600 mcg. Se recomienda limitar el número de dosificaciones diarias a un máximo de cuatro. Si el paciente sufre más de 4 episodios de dolor irruptivo al día, durante más de cuatro días consecutivos, se valorará la necesidad de reajustar la dosis de los comprimidos de fentanilo o de incrementar la dosis del analgésico opiáceo de larga duración (en cuyo caso, podría ser necesario reducir la dosis de mantenimiento de fentanilo de acción rápida)

Si durante la administración se aprecian signos de intoxicación opiácea (mareos, náuseas), se suspenderá la administración y se estudiará la necesidad de reducir la posología.

Suspensión del tratamiento: El tratamiento se interrumpirá cuando no sea necesario para eliminar el dolor irruptivo. En caso de suspensión, se valorará la posibilidad de que aparezca un síndrome de abstinencia.

– Niños y adolescentes menores de 18 años, bucal: No se ha evaluado la seguridad y eficacia.

– Ancianos, bucal: Se ha comprobado que los pacientes mayores de 65 años suelen ser más sensibles a los efectos de fentanilo intravenoso que la población más joven. En ancianos puede haber una acumulación de fentanilo, por lo que se aconseja precaución. POSOLOGÍA EN INSUFICIENCIA RENAL Puede haber disminución del aclaramiento sistémico. Se aconseja monitorizacion rigurosa durante el proceso de titulación de la dosis. POSOLOGÍA EN INSUFICIENCIA HEPÁTICA Puede haber disminución del aclaramiento sistémico. Se aconseja monitorizacion rigurosa durante el proceso de titulación de la dosis.

Normas Para La Correcta Administración

– Comprimidos para chupar: Los comprimidos se colocarán entre la encía y la cara interna de la mejilla, y con la ayuda del aplicador se frotarán contra la mejilla. Los comprimidos se chuparán durante un período de unos 15 minutos, sin masticarlos ni partirlos, ya que podrían reducirse los efectos. Es aconsejable beber un vaso de agua antes de la administración, para favorecer la hidratación de la mucosa oral. Una vez que se inicie la administración se deberá evitar beber o comer nada.

– Hipersensibilidad al fentanilo, [ALERGIA A OPIOIDES] o a cualquier otro componente del medicamento.

– Depresión respiratoria o enfermedad pulmonar obstructiva grave, ante el riesgo de aumentar la depresión respiratoria.

– Daño grave del sistema nervioso central.

– Pacientes tratados con IMAO en los últimos 14 días (véase Interacciones).

– [INSUFICIENCIA RENAL]. El fentanilo se excreta en pequeña cantidad inalterado con la orina, y no parece hacerlo en forma de metabolitos activos. Sin embargo, en pacientes sometidos a hemodiálisis se ha observado una modificación del volumen de distribución, y por tanto de las concentraciones plasmáticas, que podría dar lugar a toxicidad.

– [DEPRESION RESPIRATORIA]. Al igual que otros opioides, el fentanilo podría dar lugar a depresión respiratoria, especialmente cuando se emplea como tratamiento de inicio en pacientes sin tolerancia previa a opioides. En aquellos pacientes con depresión respiratoria previa, enfermedades que puedan predisponer a la misma ([MIASTENIA GRAVE]), así como en enfermedades pulmonares como [ASMA] o [ENFERMEDAD PULMONAR OBSTRUCTIVA CRONICA], en los que el fentanilo podría reducir el estímulo respiratorio e incrementar la resistencia al flujo de aire, se aconseja utilizar con mucha precaución. En casos graves se aconseja evitar su utilización (véase Contraindicaciones).

– Cardiopatías. El fentanilo puede producir depresión del centro vasomotor, por lo que se recomienda extremar las precauciones en pacientes con [BRADICARDIA] o [HIPOTENSION], así como en [HIPOVOLEMIA].

– [TRAUMATISMO CRANEOENCEFALICO]. El fentanilo podría incrementar la presión del líquido cefalorraquídeo, por lo que podría agravar el estado físico de pacientes con traumatismo craneoencefálico, [HIPERTENSION INTRACRANEAL], inconsciencia o [COMA]. Se recomienda extremar las precauciones en estos casos, así como en [TUMOR CEREBRAL]. El fentanilo podría además enmascarar la sintomatología de estas enfermedades. En caso de enfermedad neurológica grave, se recomienda evitar su utilización (véase Contraindicaciones).

– [OBSTRUCCION INTESTINAL]. Como otros opioides, el fentanilo podría reducir el peristaltismo intestinal.

– [DEPENDENCIA A OPIACEOS]. El fentanilo, como cualquier otro opioide, puede dar lugar a fenómenos de dependencia física y psíquica, así como tolerancia. Si bien es raro que se produzca adicción por su utilización médica, no se puede descartar, por lo que se recomienda vigilar estrechamente su utilización en pacientes con historial de [DROGODEPENDENCIA].

– [HIPERPLASIA BENIGNA DE PROSTATA]. Los opiáceos pueden favorecer la retención de orina, empeorando la sintomatología en estos pacientes.

– [HIPOTIROIDISMO]. En estos pacientes es mayor el riesgo de depresión nerviosa y respiratoria.

– [ULCERA BUCAL]. Los pacientes con daños en la mucosa oral, como en caso de ulceraciones o [MUCOSITIS ORAL], podrían ver incrementada la exposición sistémica del fentanilo administrado por vía bucal.

PRECAUCIONES RELATIVAS A EXCIPIENTES – Este medicamento contiene sacarosa. Los pacientes con [INTOLERANCIA A FRUCTOSA] hereditaria, malaabsorción de glucosa o galactosa, o insuficiencia de sacarasa-isomaltasa, no deben tomar este medicamento.

– Este medicamento contiene etanol. Se recomienda revisar la composición para conocer la cantidad exacta de etanol por dosis.

* Cantidades inferiores a 100 mg/dosis se consideran pequeñas y no suelen ser perjudiciales, especialmente en niños.

* Cantidades superiores a 100 mg/dosis pueden resultar perjudiciales para personas con [ALCOHOLISMO CRONICO], y deberá ser tenido en cuenta igualmente en mujeres embarazadas y lactantes, niños, y en grupos de alto riesgo, como pacientes con enfermedad hepática ([INSUFICIENCIA HEPATICA], [CIRROSIS HEPATICA], [HEPATITIS]) o [EPILEPSIA].

* Cantidades superiores a 3 g/dosis podrían disminuir la capacidad para conducir o manejar maquinaria, y podría interferir con los efectos de otros medicamentos.

– Este medicamento contiene glucosa. Los pacientes con malaabsorción de glucosa o galactosa, no deben tomar este medicamento.

– Este medicamento contiene glucosa. Su uso en líquidos orales y formas farmacéuticas que permanezcan un tiempo en contacto con la boca puede perjudicar a los dientes.

– Este medicamento contiene sacarosa. Su uso en líquidos orales y formas farmacéuticas que permanezcan un tiempo en contacto con la boca puede perjudicar a los dientes.

>> Los inhibidores potentes o moderados del CYP3A4 (ej: ciertos antibióticos macrólidos como eritromicina y claritromicina, antifúngicos azólicos como ketoconazol, itraconazol y fluconazol y ciertos inhibidores de proteasa, como ritonavir) pueden incrementar los efectos y potenciar la depresión respiratoria.

>> Sólo debe usarse en dolor irruptivo en pacientes adultos que ya reciben tratamiento con opiáceos para dolor crónico en cáncer.

>>La sustitución de fentanilo citrato comprimidos para chupar por cualquier otro producto con fentanilo puede resultar en sobredosis de consecuencias fatales.

* No sustituir fentanilo citrato comprimidos para chupa por otro producto con fentanilo. Debido a los diferentes perfiles de absorción, el cambio no se debe efectuar guardando una relación 1:1 (se requiere una titulación independiente de la dosis).

– El riesgo de depresión respiratoria es especialmente significativo si se usa el fentanilo en pacientes que no hayan recibido previamente un opiáceo. Se aconseja no usar los comprimidos en estos pacientes; los parches pueden emplearse, pero limitando la dosis de inicio a la mínima posible.

– Fentanilo bucal puede causar depresión respiratoria de conscuencias fatales si no se utiliza de la forma que aconseja la ficha técnica. >> Los comprimidos de fentanilo llevan una cantidad muy importante de fármaco, que puede producir una intoxicación mortal en niños. Se recomienda mantener fuera de su alcance.

– El fentanilo puede producir somnolencia, por lo que se extremarán las precauciones al conducir.

– Se recomienda evitar el consumo de bebidas alcohólicas durante el tratamiento.

– Se recomienda extremar las precauciones y no tener el fentanilo al alcance de los niños, especialmente los más pequeños, ante el riesgo de intoxicación potencialmente mortal.

– Se recomienda advertir al médico y/o farmacéutico si aparece dificultad para respirar, mareos o somnolencia demasiado intensa durante el tratamiento.

– El tratamiento de los brotes de dolor con fentanilo se utilizará sólo en aquellos pacientes cuyo dolor esté controlado.

– Antes de administrar los comprimidos, se recomienda beber un vaso de agua.

– No se beberá ni comerá nada mientras se administra el medicamento.

– El tratamiento del dolor irruptivo se suspenderá tan pronto como no sea necesario.

– Se recomienda no administrar más de 4 comprimidos diarios. Si el paciente necesitase mayor dosis, se consultará con el médico y/o farmacéutico.

– Alcohol. El alcohol podría potenciar los efectos centrales del fentanilo, aumentando el riesgo de depresión nerviosa y respiratoria profunda. Se recomienda evitar la asociación.

– Antagonistas o agonistas parciales opiáceos. La administración de fentanilo con un antagonista (naloxona, naltrexona) o agonista parcial (buprenorfina, butorfanol, pentazocina) podría reducir los efectos y desencadenar un síndrome de abstinencia. Se recomienda evitar la asociación.

– Fármacos hipnosedantes (anestésicos generales, antihistamínicos, antipsicóticos, barbitúricos, benzodiazepinas, otros opioides). Podría incrementarse el riesgo de depresión nerviosa. Se han descrito casos de sedación profunda, hipotensión, bradicardia, depresión respiratoria y coma, que podrían ser potencialmente fatales. Se recomienda extremar las precauciones.

– IMAO. Se han descrito casos en los que los IMAO incrementaron intensamente los efectos depresores del fentanilo, de manera impredecible. Se recomienda evitar la utilización de este medicamento en pacientes que hayan recibido un IMAO los 14 días anteriores.

– Inhibidores del CYP3A4 (antifúngicos azólicos, inhibidores de la proteasa, macrólidos, zumo de pomelo). El fentanilo se metaboliza extensamente en hígado a través del CYP3A4, por lo que los fármacos inhibidores de este sistema enzimático podrían incrementar los niveles plasmáticos de fentanilo, con el consiguiente riesgo de sobredosificación. Se recomienda evitar la utilización de fentanilo transdérmico en pacientes tratados con inhibidores potentes, como itraconazol o ritonavir debido al riesgo de depresión respiratoria prolongada. En el caso de fentanilo bucal, al ser sus efectos más limitados en el tiempo, podría ser necesario ajustar la dosis con precaución y vigilar al paciente. EMBARAZO Categoría C de la FDA. La utilización del fentanilo en ratas y conejas preñadas no ocasionó efectos teratógenos, aunque sí se ha observado un aumento de las muertes embrionarias en las ratas. No obstante, el efecto parece ser debido más a la propia toxicidad materna que al efecto directo de la sustancia sobre el feto.

No se dispone de estudios adecuados y bien controlados en humanos. El fentanilo puede atravesar la placenta debido a su gran liposolubilidad. La relación de concentración entre plasma fetal y materno es de 0,44. Se han descrito síndromes de abstinencia (irritabilidad, hiperactividad, temblores, taquipnea, diaforesis) y depresión respiratoria en neonatos de madres que tomaron opiáceos, incluido fentanilo, durante el embarazo y el parto. Los riesgos parecen mayores en niños con distrés respiratorio y acidosis, debido a que el fentanilo queda retenido en sangre fetal. Si el pH materno y el fetal son similares, el fentanilo tiende a pasar a la sangre materna y ser metabolizado.

La administración de fentanilo sólo se acepta durante el embarazo en el caso de que no existiendo alternativas terapéuticas más seguras, los beneficios superen los posibles riesgos. Sería recomendable evitar su empleo durante el parto, ante el riesgo de depresión respiratoria profunda.

Efectos sobre la fertilidad: El fentanilo no afectó a la fertilidad masculina, pero disminuyó la de las hembras a dosis intravenosas 0,3 veces las humanas, administradas durante 12 días. LACTANCIA El fentanilo se excreta con la leche materna, apareciendo en el calostro a concentraciones de 0,4 ng/ml, que se hicieron indetectables al cabo de 10 h. El fabricante aconseja suspender la lactancia por lo menos hasta pasadas 24 h de la última dosis de fentanilo (que podría ser un período aún mayor en el caso de los parches, debido a la gran semivida del fentanilo), ante el riesgo de depresión nerviosa y respiratoria en el lactante.

No obstante, la Academia Americana de Pediatría considera al fentanilo compatible con la lactancia, debido a los bajos niveles alcanzados en calostro y a la pequeña biodisponibilidad oral que presenta, como consecuencia de su intenso efecto de primer paso. NIÑOS No se ha evaluado la seguridad y eficacia en niños y adolescentes menores de 18 años. Ante el riesgo de intoxicación potencialmente fatal se recomienda evitar su utilización. ANCIANOS Los pacientes mayores de 65 años suelen mostrar una reducción del aclaramiento del fentanilo, y además son más sensibles a los efectos de los opiáceos, tanto los terapéuticos como los secundarios. Se recomienda ajustar la dosis con especial precaución. EFECTOS SOBRE LA CONDUCCIÓN El fentanilo puede producir vértigo y depresión nerviosa importante, afectando de manera muy sustancial a la capacidad para conducir y/o manejar maquinaria. Los pacientes deberán evitar manejar maquinaria peligrosa, incluyendo automóviles, hasta que haya pasado el tiempo suficiente como para tener la certeza razonable de que el tratamiento farmacológico no les afectará de forma adversa. REACCIONES ADVERSAS El fentanilo tiene una serie de efectos secundarios de grupo, comunes con el resto de los opiáceos, y entre los que destacan por su gravedad la depresión respiratoria, incluso con parada respiratoria, la bradicardia e hipotensión y el shock circulatorio. Estas reacciones adversas son dosis-dependientes, y aparecen especialmente en personas con poca tolerancia a opioides, disminuyendo su incidencia con el tiempo de utilización. Además de estas reacciones adversas, las más comúnmente comunicadas son náuseas y vómitos, estreñimiento, cefalea, somnolencia y fatiga y mareos.

– Digestivas: (>10%) [NAUSEAS]; (1-10%) [VOMITOS], [DOLOR ABDOMINAL], [ESTREÑIMIENTO], [DIARREA], molestias abdominales, [DISPEPSIA], [SEQUEDAD DE BOCA], [ANOREXIA], [OBSTRUCCION INTESTINAL], [DISFAGIA]; (0,1-1,0%) [DISTENSION ABDOMINAL], [FLATULENCIA], [POLIDIPSIA]; (0,01-0,1%) [HIPO]. Se han comunicado casos de [ULCERA BUCAL], [ESTOMATITIS], alteraciones de la lengua.

– Cardiovasculares: (1-10%) [RUBORIZACION], [SOFOCOS], [HIPOTENSION ORTOSTATICA], [VASODILATACION PERIFERICA]; (0,1-1,0%) [HIPERTENSION ARTERIAL], [BRADICARDIA], [TAQUICARDIA]; (<0 cardiaca="" span="">

- Neurológicas/psicológicas: (>10%) [MAREO], [SOMNOLENCIA], [CEFALEA]; (1-10%) [INSOMNIO], [DISGEUSIA], [DEPRESION], [CONFUSION], [ANSIEDAD], [NERVIOSISMO], [ALUCINACIONES], [TRASTORNOS DEL SUEÑO], [EUFORIA], [PARESTESIA], [HIPOESTESIA], [HIPERACUSIA], reacciones vasovagales, [DISMINUCION DE LA CONCENTRACION], [MIOCLONIA]; (0,1-1,0%) [VERTIGO], [AMNESIA], [TEMBLOR], [AFASIA], [ATAXIA], [AGITACION], despersonalización.

– Respiratorias: (1-10%) [RINITIS], [FARINGITIS], [DEPRESION RESPIRATORIA]; (0,1-1,0%) [ASMA], [DISNEA], [HIPOVENTILACION];

- Urinarias: (1-10%) [INFECCION GENITOURINARIA]; (0,1-1,0%) [RETENCION URINARIA] y cambios en la frecuencia urinaria;

- Dermatológicas: (>10%) [EXCESO DE SUDORACION]; (1-10%) [ERUPCIONES EXANTEMATICAS], [PRURITO].

– Endocrinos: (0.1-1%): [HIPOGONADISMO]. Frecuencia desconocida, insuficiencia suprarrenal, deficiencia

– Oftalmológicas: (1-10%) [TRASTORNOS DE LA VISION], [CONJUNTIVITIS].

– Generales: (>10%) [ASTENIA], [EDEMA MALEOLAR]; (0,1-1,0%) [MALESTAR GENERAL]. Riesgo de síndrome de abstinencia neonatal.

– Hipersensibilidad: rara vez, prurito, eritema, edema labial y facial y urticaria.

Síntomas: La sobredosis por fentanilo da lugar a una potenciación de sus efectos farmacológicos, siendo el síntoma más grave y preocupante la depresión respiratoria y nerviosa que puede producir, y que puede dar lugar a muerte por parada cardiorrespiratoria.

Tratamiento: En caso de síntomas de sobredosis, se suspenderá inmediatamente la administración de opiáceos. El antídoto en caso de sobredosis por opiáceos es la naloxona, o cualquier otro antagonista opiáceo. Teniendo en cuenta que la duración de los efectos de la naloxona puede ser menor que la duración de la depresión respiratoria, podría ser necesario repetir la dosis del antagonista. Deberá valorarse la necesidad de naloxona en pacientes que hayan recibido opiáceos de manera prolongada ya que podría desencadenar un síndrome de abstinencia.

Se intentará estimular física y verbalmente al paciente. En caso de que se aprecie inconsciencia y depresión respiratoria, se procederá a intubar y realizar respiración mecánica con administración de oxígeno.

En caso de que se produzca hipotensión grave, se valorará la posible hipovolemia y se administrarán fluidos parenterales en caso de ser necesario.

Es aconsejable igualmente vigilar el estado de consciencia del paciente, así como su temperatura.

Finalmente, si se produjese rigidez muscular que pudiera interferir con la respiración, se administrarán relajantes musculares. DOPAJE El fentanilo es una sustancia prohibida durante la competición.

Se considera sustancia específica y, por tanto, una violación de la norma en la que esté involucrada esta sustancia puede ocasionar una reducción de sanción siempre y cuando el deportista pueda demostrar que el uso de la sustancia específica en cuestión no fue con intención de aumentar su rendimiento deportivo. Este medicamento contienen alcohol. Está prohibida su ingesta durante la competición en ciertos deportes. La detección se realizará por análisis de aliento y/o de la sangre. El umbral de violación de norma antidopaje (valor hematológico) es de 0,1 g/l en los siguientes deportes: aeronáutica, automovilismo, motociclismo, motonáutica y tiro con arco.

El alcohol se considera sustancia específica y, por tanto, una violación de la norma en la que esté involucrada esta sustancia puede ocasionar una reducción de sanción siempre y cuando el deportista pueda demostrar que el uso de la sustancia específica en cuestión no fue con intención de aumentar su rendimiento deportivo.