Prehospital Fluid Management in Hemorrhagic Shock by jems.com

Prehospital Fluid Management in Hemorrhagic Shock.

"A survey of EMS medical direction practice"

Hemorrhagic shock is a clinical state in which severe blood loss causes insufficient cellular oxygen delivery, leading to organ failure and, ultimately, death.1 Annually, over 60,000 deaths in the United States and some 1.9 million worldwide are due to hemorrhagic shock, with some 1.5 million of these cases associated with trauma.2,10

IV fluid resuscitation has become a staple of prehospital management of hemorrhagic shock. However, subsequent studies from both laboratory control models and post-transport patient outcomes have questioned this practice, suggesting that permissive hypotension (i.e., systolic blood pressure [SBP] of 80 mmHg or below in adults) or resuscitation with blood products leads to improved patient outcomes and survival.

It’s unclear whether, despite this evolving body of work, these recommendations have been broadly adopted by civilian EMS practices in the prehospital setting.

The authors surveyed the medical directors of many large EMS systems to determine whether the practice of permissive hypotension or the administration of prehospital blood products has been more widely adopted.

Methods

A survey was sent to the EMS medical directors of many large EMS systems (the “Eagles Coalition”) who were asked two questions: 1) Whether their system used blood or blood products during the prehospital resuscitation phase of hemorrhagic shock management; and 2) The blood pressure targets, if relevant, associated with their hemorrhagic shock resuscitation protocol.

For categorization of results, we defined the maintenance of SBP of 80 mmHg or less—or mean arterial pressure (MAP) of 45–50 mmHg or less—as “permissive hypotension.”

We excluded head trauma or pediatric resuscitation protocols, interpreting only traumatic hemorrhagic shock—both penetrating and blunt force—survey results.

Results

Of the polled group, 22 members responded to the survey. Resuscitation protocols weren’t consistent within the group, with four (4) general methods reported as resuscitation targets. 61% of respondents administer fluids to a predetermined target SBP, 5% to a target MAP, 5% to a palpable radial pulse, and 29% allow permissive hypotension.

Within the SBP group, SBP targets range from a low of 70 mmHg to a high of 100 mmHg, with the majority of respondents choosing a SBP resuscitation target of 90 mmHg.

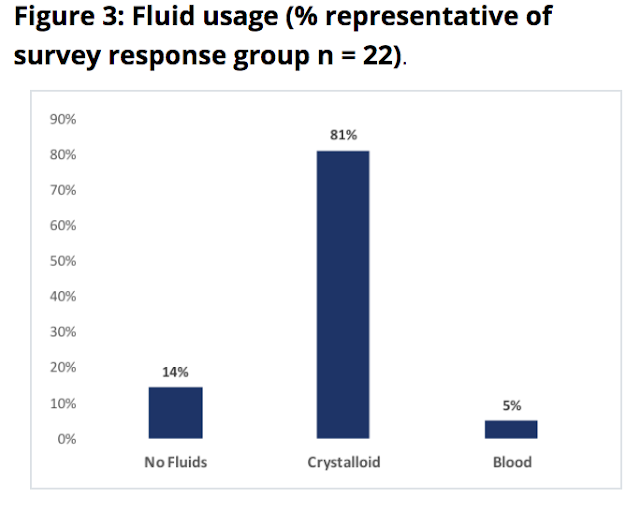

With respect to fluid administration, 14% of the respondent group use no fluid resuscitation (i.e., employing strict permissive hypotension), 81% use crystalloid product (i.e., defined as normal saline or lactated ringers solution), and 5% use blood products. Results are summarized in Figures 1, 2 and 3 below.

Discussion

Our study indicates that a generally accepted prehospital protocol with respect to the management of hemorrhagic shock remains the subject of considerable debate. Data continue to suggest that limiting the use of crystalloid is a more optimal strategy for management of hemorrhagic shock, preserving normothermia and preventing excessive dilution of both red blood cell volume and clotting factors.13–16,19–23

Additionally, it’s apparent from clinical experience gained both in civilian centers and in military theaters that the administration of blood and blood products to patients in hemorrhagic shock is associated with improved patient outcomes.13,14

Moreover, 10-year trends of crystalloid administration secondary to hemorrhagic shock have been in decline, and civilian EMS system administration of blood and blood products has been determined as a feasible prehospital practice.17,18

Still, it appears that the practice has not been widely adopted by EMS organizations, as only 5% of respondents in our survey employed the administration of blood and blood products.

The hesitation to provide for the administration of blood and blood products in EMS systems to patients with hemorrhagic shock is understandable given the complexity of the issues involved: Storage, cost, handling (including transport and refrigeration where necessary) and expiration dates.

Nonetheless, advancing evidence suggests that blood and blood product administration is superior to crystalloid in the management of hemorrhagic shock.

This study has several limitations, including the stratification of resuscitation protocols as regards to hemorrhagic shock resuscitation in the presence and absence of head injury, and it doesn’t explore the resuscitative management of pediatric patients. Still, these data provide perspective on the current practice environment on this clinical issue among large EMS systems.

Conclusion

Despite the growing body of evidence supporting the use of blood and blood products in the prehospital resuscitation of patients with hemorrhagic shock, few EMS systems employ these treatments at this time.

The complexity of issues involved with the administration of blood and blood products to these patients bears additional study, which may better inform and influence practice change in the prehospital setting.

References

1. Savasta S, Marchi A, Bianchi E, et al. Hemorrhagic shock and encephalopathy: Diagnostic criteria. Am J Dis Child. 1992;146(3):279.

2. Cannon JW. Hemorrhagic shock. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(4):370–379.

3. Bickell WH, Wall MJ Jr, Pepe PE, et al. Immediate versus delayed fluid resuscitation for hypotensive patients with penetrating torso injuries. N Engl J Med. 1994;331(17):1105–1109.

4. Barkana Y, Stein M, Maor R, et al. Prehospital blood transfusion in prolonged evacuation. J Trauma. 1999;46(1):176–180.

5. Stern SA. Low-volume fluid resuscitation for presumed hemorrhagic shock: Helpful or harmful? Curr Opin Crit Care. 2001;7(6):422–430.

6. Gou DY1, Zhu YF, Jin Y, et al. Spontaneous diuresis and negative fluid balance predicting recovery and survival in patients with trauma-hemorragic shock. Chin J Traumatol. 2003;6(6):382–384.

7. Mauriz JL, Martín Renedo J, Barrio JP, et al. [Experimental models on hemorrhagic shock.] Nutr Hosp. 2007;22(2):190–198.

8. Dawes R, Thomas Go. Battlefield resuscitation. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2009;15(6):527–535.

9. Durusu M, Eryilmaz M, Oztürk G, et al. Comparison of permissive hypotensive resuscitation, low-volume fluid resuscitation, and aggressive fluid resuscitation therapy approaches in an experimental uncontrolled hemorrhagic shock model. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2010;16(3):191–197.

10. Curry N, Hopewell S, Dorée C, et al. The acute management of trauma hemorrhage: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Crit Care. 2011;15(2):R92.

11. Haut ER, Kalish BT, Cotton BA, etc. Prehospital intravenous fluid administration is associated with higher mortality in trauma patients: A National Trauma Data Bank analysis. Ann Surg. 2011;253(2):371–377.

12. Bhangu A, Nepogodiev D, Doughty H, et al. Meta-analysis of plasma to red blood cell ratios and mortality in massive blood transfusions for trauma. Injury. 2013;44(12):1693–1699.

13. O'Reilly DJ, Morrison JJ, Jansen JO, et al. Prehospital blood transfusion in the en route management of severe combat trauma: a matched cohort study. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;77(3 Suppl 2):S114–S120.

14. Holcomb JB, Donathan DP, Cotton BA, et al. Prehospital transfusion of plasma and red blood cells in trauma patients. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2015;19(1):1–9.

15. Copotoiu R, Cinca E, Collange O, et al. [Pathophysiology of hemorragic shock]. Transfus Clin Biol. 2016;3(4):222–228.

16. Driessen A, Fröhlich M, Schäfer N, et al. Prehospital volume resuscitation--Did evidence defeat the crystalloid dogma? An analysis of the TraumaRegister DGU(R) 2002–2012. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med. 2016;24: 42.

17. Harada MY, Ko A, Barmparas G, et al. 10-year trend in crystalloid resuscitation: Reduced volume and lower mortality. Int J Surg. 2017;38:78–82.

18. Bodnar D, Rashford S, Williams S, et al. The feasibility of civilian prehospital trauma teams carrying and administering packed red blood cells. Emerg Med J. 2014;31(2):93–95.

19. Kheirabadi BS, Miranda N, Terrazas IB, et al. Does small-volume resuscitation with crystalloids or colloids influence hemostasis and survival of rabbits subjected to lethal uncontrolled hemorrhage? J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;82(1):156–164.

20. László I, Demeter G, Öveges N, et al. Volume-replacement ratio for crystalloids and colloids during bleeding and resuscitation: an animal experiment. Intensive Care Med Exp. 2017;5(1):52.

21. Maegele M, Fröhlich M, Caspers, et al. Volume replacement during trauma resuscitation: a brief synopsis of current guidelines and recommendations. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2017;43(4):439–443.

22. Zhao G, Wu W, Feng QM, et al. Evaluation of the clinical effect of small-volume resuscitation on uncontrolled hemorrhagic shock in emergency. Ther Clin Risk Manag. 2017;13:387–392.

23. Holcomb J. Combative behaviors: Translocating military medicine research into civilian lifesaving [presentation]. Gathering of Eagles: The EMS State of the Science Conference: Dallas, 2018.

By

Raymond L. Fowler, MD, FACEP, FAEMS

Raymond L. Fowler, MD, FACEP, FAEMS, is the James M. Atkins MD Professor of EMS and chief of the Division of EMS at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas. He's been involved in EMS as a leading educator, author, medical director, and political advocate for more than four decades, and is a member of the JEMS Editorial Board.

Reed Macy, BA

Reed Macy, BA, is a fourth-year medical student at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center and an upcoming emergency medicine resident.

Gil Salazar, MD, FACEP

Gil Salazar, MD, FACEP, is the director of the section on EMS education at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.

Hunter Pyle, BBA

Hunter Pyle, BBA, is a first-year medical student at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.

by Enfermeriacreativa https://enfermeriacreativa.com/2017/12/18/shock-hemorragico/

Existen diversos tipos de shock y entre ellos, encontramos el shock hipovolémico que se divide en shock hemorrágico y no hemorrágico. Puedes ver la clasificación de los tipos de shock aquí.

El shock hemorrágico se caracteriza por:

Pérdida masiva extravascular de sangre, lo que provoca una disminución del volumen sanguíneo.

La hemorragia puede ser tanto interna como externa.

Suele ser el tipo de shock más frecuente, ya que puede darse en intervenciones quirúrgicas, traumatismos, hemorragias obstétricas o digestivas.

Durante su fase inicial, la gravedad del shock hemorrágico está relacionada con el volumen de sangre perdido. El American College of Surgeons Advanced Trauma Life Support Manual define cuatro estadios de gravedad en el shock (I-IV) . Por ello, he realizado una infografía lo más visual posible, para que puedas entender y memorizar más fácilmente esta clasificación.

Clasificación American College of Surgeons

Fuentes:

Ronald D. Miller. (2016). Manejo de la sangre del paciente: terapia transfusional.

En Miller Anestesia(1830-1867). España: Elsevier.

Shock hemorrágico. Anestesia-Reanimación, 2010-01-01, Volumen 36, Número 3, Páginas 1-22. 2010 Elsevier Masson SAS

[Última actualización 27/02/2018]

Todas nuestras publicaciones sobre Covid-19 en el enlace

AVISO IMPORTANTE A NUESTROS USUARIOS

Este Blog va dirigido a profesionales de la salud y publico en general EMS Solutions International garantiza, en la medida en que puede hacerlo, que los contenidos recomendados y comentados en el portal, lo son por profesionales de la salud. Del mismo modo, los comentarios y valoraciones que cada elemento de información recibe por el resto de usuarios registrados –profesionales y no profesionales-, garantiza la idoneidad y pertinencia de cada contenido.

Es pues, la propia comunidad de usuarios quien certifica la fiabilidad de cada uno de los elementos de información, a través de una tarea continua de refinamiento y valoración por parte de los usuarios.

Si usted encuentra información que considera erronea, le invitamos a hacer efectivo su registro para poder avisar al resto de usuarios y contribuir a la mejora de dicha información.

El objetivo del proyecto es proporcionar información sanitaria de calidad a los individuos, de forma que dicha educación repercuta positivamente en su estado de salud y el de su entorno. De ningún modo los contenidos recomendados en EMS Solutions International están destinados a reemplazar una consulta reglada con un profesional de la salud.

No hay comentarios:

Publicar un comentario