|

| ALERGIAS, ANAFILAXIA, ASMA |

"Recordar que en las nuevas guías de primeros auxilios en caso de Alergias Severas solo se podrá administrar la primera dosis de adrenalina (1-10000), para la 2ª dosis solo podrá ser administrada por un equipo medico entrenado".

by Dr.Ramón Reyes,MD Anafilaxia en 2025: lo que NO puede fallar en urgencias y UCI ⚡🧬 🌍 ¿Por qué importa este artículo? La anafilaxia sigue siendo subdiagnosticada, infratratada y frecuentemente mal manejada, incluso en hospitales. Este artículo 2025 resume de manera magistral qué hacer, qué evitar y cómo mejorar la supervivencia, con mensajes extremadamente prácticos para la guardia. 🩺 ¿Cómo se reconoce una anafilaxia (de verdad)? El artículo insiste en algo clave: la anafilaxia es un diagnóstico clínico, no depende de laboratorios. Los datos que más pesan: • Aparición rápida de síntomas después de un desencadenante. • Compromiso respiratorio (estridor, broncoespasmo, disnea). • Compromiso cardiovascular (hipotensión, síncope, shock). • Cutáneos (urticaria, flushing) → presentes en muchos, pero no obligatorios. 📌 Importante: un paciente puede estar en anafilaxia sin rash. 💉 Adrenalina: el pilar absoluto del tratamiento ✔ Vía IM en muslo = estándar • Dosis 0.3–0.5 mg adultos. • Repetir cada 5–15 min si no hay respuesta. ✔ ¿Cuándo usar adrenalina IV? • Shock refractario a IM + fluidos. • Debe ser administrada por equipo entrenado → infusión titulada. ✔ Errores frecuentes (el artículo los recalca fuerte): • Dar antihistamínicos antes que adrenalina. • Pensar que “mejoró un poco” = no usar adrenalina. • Subdosificar. • Demorar el tratamiento por esperar laboratorio. 💧 Fluidos: más importantes de lo que se cree La anafilaxia severa produce vasodilatación extrema + fuga capilar. → Puede requerir 1–2 L de cristaloides rápidamente. El artículo enfatiza que muchos fallecimientos ocurren por no reponer volumen suficiente. ✨ Antihistamínicos y corticoides: no salvan vidas • Son coadyuvantes, NO tratamiento principal. • No previenen bifásica. • Su uso nunca debe retrasar la adrenalina. 🫁 Manejo respiratorio y cardiovascular avanzado • Broncoespasmo severo → salbutamol, adrenalina nebulizada. • Shock refractario → adrenalina IV titulada. • Edema de vía aérea → considerar intubación temprana. 📌 El artículo recalca que la vía aérea debe asegurarse antes de que sea imposible. ⏳ Anafilaxia bifásica: ¿cuánto observar? • La mayoría ocurre dentro de 4–6 horas. • El artículo sugiere observación según gravedad inicial: • Leve: 2–4 h • Moderada: 6 h • Severa / shock / adrenalina repetida: ≥ 12–24 h 🧬 Diagnóstico y herramientas adicionales ✔ Triptasa • Útil pero no necesaria para diagnóstico. • Puede apoyar cuando: • Shock inexplicado • Diagnóstico dudoso • Sospecha de mastocitosis ✔ Alergología Todo paciente con anafilaxia debe ser referido a especialista para: • Identificar desencadenante. • Evaluar riesgo futuro. • Considerar inmunoterapia. 📦 Kit de alta: el artículo lo enfatiza • Prescribir autoinyector de adrenalina. • Educación del paciente. • Enseñar técnica. • Plan escrito de acción. Este paso es tan importante como el manejo agudo. ⚡ Aplicabilidad rápida en urgencias / UCI • 🟣 Sospecha → adrenalina IM de inmediato (sin esperar nada más). • 💧 Shock = fluido abundante + adrenalina IM/IV. • 🚫 No perder tiempo con solo antihistamínicos o corticoides. • 🛑 No subestimar pacientes SIN rash. • 🧬 Derivar a alergología y siempre dar autoinyector en el alta. ❇️ Artículo completo 📲 Telegram 👉 https://t.me/medicinapublica La anafilaxia es un trastorno en el cual se produce una liberación rápida de mediadores químicos con acciones biológicas potentes derivadas de células inflamatorias como los mastocitos y basófilos que provocan síntomas cutáneos, respiratorios, cardiovasculares y gastrointestinales. Las causas más frecuentes de anafilaxia en niños difieren dependiendo de que la población estudiada represente pacientes ingresados en un servicio hospitalario o ambulatorios. La anafilaxia que se produce en el hospital se debe sobre todo a reacciones alérgicas a medicamentos y al látex, mientras que la alergia alimentaria es la causa más común de anafilaxia fuera del hospital y supone alrededor de la mitad de las reacciones anafilácticas publicadas en estudios pediátricos en los Estados Unidos, Italia y sur de Australia. La alergia al cacahuete se ha convertido en la principal causa de anafilaxia inducida por alimentos en los países “occidentalizados” , y es responsable de la mayoría de las reacciones mortales y casi mortales. Dentro del ámbito hospitalario el látex es un problema particular en niños sometidos a múltiples intervenciones quirúrgicas, como por ejemplo los que tienen espina bífida y trastornos urológicos, y ha llevado a muchos hospitales a emplear productos sin látex. Los pacientes con alergia al látex también pueden experimentar reacciones alérgicas a alimentos por proteínas homólogas presentes en frutas como la banana, el kiwi, la nuez, y la frutilla. ANAFILAXIA - Guías mundiales sobre manejo de anafilaxia

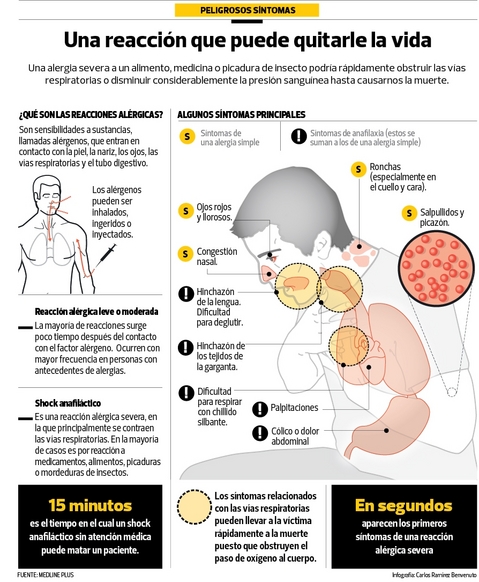

La anafilaxia se define como una reacción de hipersensibilidad sistémica o generalizada, con riesgo vital. Resumimos las guías de manejo de la anafilaxia de la Organización Mundial de Alergias.

Los factores que aumentan el riesgo de una anafilaxia severa o fatal son el asma (u otra enfermedad respiratoria crónica), las enfermedades cardiovasculares, la mastocitosis, las enfermedad a tópicas severas (como la rinitis alérgica), el uso de betabloqueadores e inhibidores de la enzima convertidora de angiotensina.

ún la edad. Los alimentos son los más comunes en los niños y adultos jóvenes. Las picaduras y los medicamentos son frecuentes en adultos de edad media y mayores. Virtualmente cualquier molécula puede producir una reacción alérgica.

El diagnóstico se basa principalmente clínico (historia y exámen físico). La historia típica es la aparición súbita de síntomas y signos característicos, luego de minutos u horas de exponerse a un potencial gatillante. Los síntomas y signos progresan en pocas horas; los más frecuentes son:

El manejo sistemático y rápido es esencial; es aplicable en cualquier momento de la crisis aguda, con cualquier gatillante y puede ser realizado por cualquier profesional médico con entrenamiento básico. El protocolo de manejo debe estar escrito, visible y constantemente revisado para que sea de utilidad. Las pruebas de laboratorio pueden ayudar a precisar el diagnóstico después de la emergencia. Se puede medir niveles de triptasa, con una muestra obtenida 15 minutos a 3 horas después del inicio del cuadro, siendo lo más recomendable la medición seriada. La triptasa generalmente está normal en anaflixia por alimentos y sin hipotensión. Los niveles de histamina se pueden obtener 15 minutos a 1 hora después del inicio, pero se requiere mantener la muestra en condiciones extremadamente complejas.

La adrenalina se utiliza como un medicamento esencial para tratar la anafliaxia, debido a sus efectos alfa-1 (vasoconstricción sintética, que produce disminución del edema de mucosas y aumenta la presión arterial), beta-1 (efecto inótropo y cronótropo) y beta-2 (broncodilatador). La administración de adrenalina es más importante que el uso de antihistamínicos y corticoides en la etapa precoz de la anafilaxia. Se debe administrar intramuscular, en el tercio medio de la cara anterolateral del muslo, tan pronto se diagnostique o sospeche fuertemente una anafilaxia, en dosis de 0,01 mg/kg (concentración de 1 mg/ml) hasta un máximo de 0,5 mg en adultos y 0,3 mg en niños. Se puede repetir la dosis cada 5-15 minutos. El retraso en la administración de adrenalina se ha asociado a mortalidad, encefalopatía hipóxico-isquémica y anafilaxia bifásica (recurrencia en 8-10 horas).

Si el paciente ya se encuentra en shock, la adrenalina se debe administrar como infusión continua intravenosa, titulando según la presión arterial y la frecuencia cardiaca. Si el paciente está en paro cardiorrespiratorio, se debe administrar adrenalina en bolos intravenosos.

Con las dosis recomendadas, se puede producir palidez, temblor, palpitaciones y cefalea. Con dosis mayores o administración intravenosa se pueden producir arritmias ventriculares, crisis hipertensas o edema pulmonar. La adrenalina no está contraindicada en pacientes con patología cardiovascular.

No están claras las recomendaciones respecto a los medicamentos de segunda línea. Las guías mundiales dicen que no está claro el rol de ninguno de ellos y son secundarion con respecto a la adrenalina.

Los casos refractarios deben ser manejados por médicos especialistas en centros médicos de alta complejidad. Si requieren intubación, debe realizarla el operador más capacitado por su alta complejidad, con una adecuada preoxigenación (3-4 minutos). Algunos pacientes requieren vasopresores por infusión contínua, pero no está claro cuál de ellos es la mejor opción. En lo pacientes que utilizan betabloqueadores, se puede utilizar glucagón. Algunos pacientes pueden requerir atropina.

Hay algunas consideraciones respecto al manejo en situaciones especiales:

Conclusiones:

Artículo fuente |

Enlace Guía-ABE visualizar y si quieres el pdf pincha aquí

Nuevas Guias RCP 2020-2025 AHA/ILCOR

o Los ácaros, animalitos microscópicos que se alimentan de la piel que descamamos y el cabello que se cae naturalmente y viven en la cama, la ropa guardada, etc.

o Algunos alimentos, entre ellos: la leche y sus derivados, los cítricos, los mariscos, maníes, nueces, soya, entre otros.

o Algunos medicamentos.

o Picaduras de insectos.

o Polen, lo que no es frecuente en República Dominicana por tener una estación casi única durante todo el año.

o Animales como los perros, gatos y las cucarachas.

1. Aún muchos dicen que las alergias no tienen cura, pero esto es falso porque la inmunoterapia es un tratamiento que científicamente ofrece la solución a este mal.

2. Las vacunas que se usan en la inmunoterapia tienen cortisona, estas vacunas sólo contienen el alergeno ante el que reacciona el paciente y solución salina.

3. Las vacunas se inyectan de forma intravenosa, si se le inyecta a un paciente alérgico, una de las vacunas con el alergeno ante el que reacciona de manera intravenosa se hace mala práctica médica y se pone en riesgo la vida de éste Las inyecciones deben hacerse de forma subcutánea y nunca intravenosa en la inmunoterapia.

4. Las alergia no suelen ser causa de muerte, pero sí pueden tener consecuencias fatales, como la anafilaxis al ser detonante de bronco espasmos, hipertensión severa, pérdida de la conciencia, cierre laríngeo y hasta ataques cardíacos en cuestiones de segundos.

o Detiene la marcha alérgica

o Elimina o disminuye de un 90 a 95% los signos, a la vez que evita que surjan nuevos síntomas.

o Evita que se afecten nuevos órganos

o Disminuye el uso de medicamentos.

o Mejora la calidad de vida del paciente.

posted by Dr. Ramon Reyes, MD ∞ 𓃗 #

𓃗 # 𓃗 @DrRamonReyesMD

𓃗 @DrRamonReyesMD